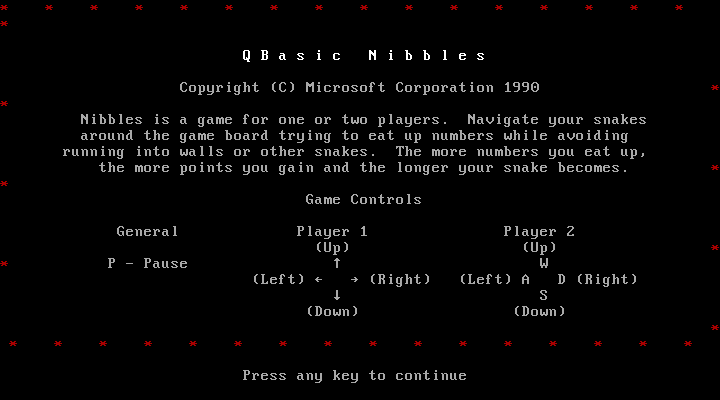

I have very fond memories of QBasic Nibbles. I spent lots of time playing that game, modifying it until it was unrecognizable, and accidentally learning how to program along the way.

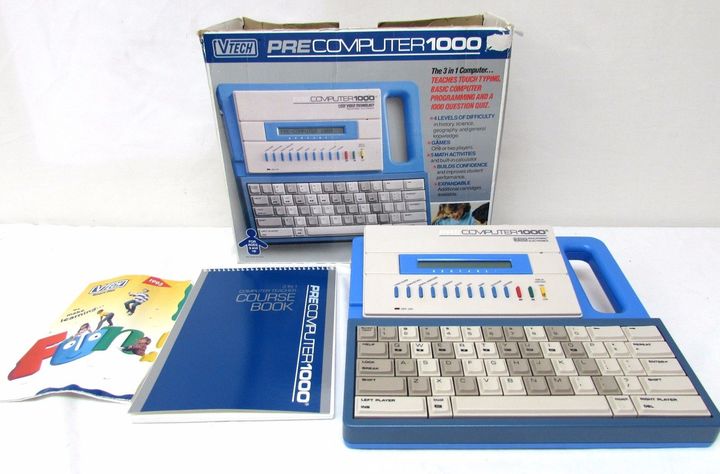

QBasic wasn’t my first introduction to programming, though. The credit for that goes to this cute little thing:

The VTech Pre-Computer 1000. It had… not much, actually. With a single-line, 20-character LCD, and no permanent storage, doing anything with it was a major challenge. Still, I painstakingly typed out the examples from the book that came with it, hunt-and-peck, letter by letter, as incoherent as most of the code was to me at the time. When I finally got something to run, I was so excited. It was more an exercise in learning the keyboard than anything, I think. With the hardware limitations, experimenting wasn’t particularly easy, and with my knowledge limitations, typing wasn’t easy either, so I mostly stuck to the shorter examples.

In middle school, I had periodic access to the Apple II systems in one of the computer labs, with green screens. (These were on the way out, and the systems in the new PC lab that they were putting in were running Windows 3.11, I think.) Once I figured out how to get into a BASIC programming environment, I was thrilled: I’d finally be able to try out those longer examples, and I could even save them! (At some point there, I had also become the proud owner of a 5¼″—a.k.a. Actually Floppy—disk.) Naturally, I started typing out the longer examples from my trusty Pre-Computer book, only to learn that, surprise, they weren’t terribly exciting. The most interesting one that I can remember was a variant of Nim, and that was only good for a couple of plays before it ceased being fun.

At this level, the best thing I could have written on my own was probably something along the lines of

10 PRINT "HELLO" 20 GOTO 10

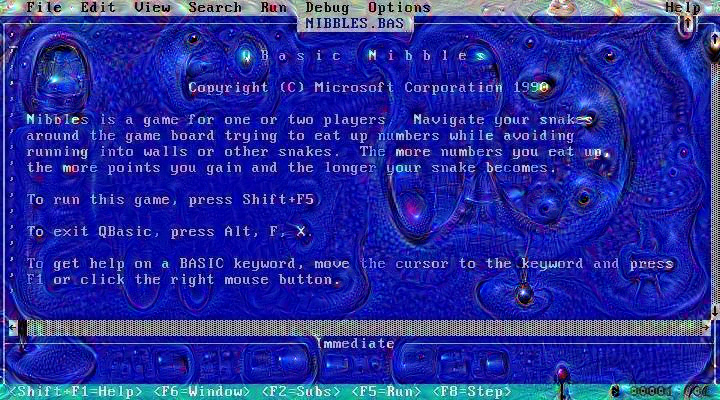

I never quite understood what I was doing, though, until I got into QBasic. It was thanks to that environment, and in particular, the help system that provided comprehensive documentation for every single keyword at a touch of the F1 key, that I really started to grasp what the heck the code was doing. I skimmed the example files that came with it:

-

GORILLA.BAShad heaps of drawing stuff with mathematics and lots of numbers, peppered with tiny bits here and there that amused me. (ExplodeGorilla!) Ultimately, it was just too complex for me at the time, and that probably fed into my interest for text-based stuff versus graphics. -

MONEY.BASwas massive and scary-looking, and on top of that, boring! Who cares about money? That’s for adults. But it had a menu bar, which was vaguely interesting, and uh… four different color schemes. Yep, still boring. -

NIBBLES.BASwas a really fun game. I’ll come back to it. -

REMLINE.BAS… actually, I don’t think I ever got past the first line of this, not that it would’ve been all that worthwhile for me anyway. (Tip: if you don’t want kids reading your code, put a comment at the top describing it as a “utility.”) Curiously, this program had a few functions that mirrored C, but I’m only now recognizing that in retrospect. As a kid, I was looking at the function names like, “StrBrk? What is this gibberish?”

So three out of four of those programs are just ~eh~. But let’s have another look at that Nibbles game, hmm? Except it always asks me for the same few things, wonder if there’s any way to skip the questions and go right to the game? Ooh, if I delete this stuff and change that thing it still works! Wonder what that does? Programming’s not so bad after all!

And at some point, I had a massive realization that if I copied the file before doing stuff, I could save it, keep what I’d changed, and if I messed up and broke everything, I’d reload the original file and all would be well. Nibbles was the first non-trivial program I had ever laid my hands on the source code for, and once I got over that irrational initial fear of destroying the computer (a necessary step—many people who are just getting started with programming seem to fear experimentation!) I proceeded to hack the heck out of that little game. I fiddled with the color palette, edited the sound effects, made the snakes rainbow colors, added more levels, modified the existing ones, rewrote the title screen, altered the keyboard input… there was not a part of that code that I hadn’t tried changing in some way or another. I made it mine.

I got a book on QBasic and started building things of my own, and somewhere along the way, I ended up learning what a heap of other languages had to offer, Visual Basic, then Perl, C, Tcl, so on and so on. At some point, it stopped being “I’d like to learn how such-and-such language works” and turned into “I wonder how this existing program works, and it uses this language,” and eventually to “I’d like to see how this language works, and how it makes me perceive my code.” That last one is such a huge leap, but I think it’s an important leap to make. I believe some form of linguistic relativism applies to computer programming: You can just kind of tell – like when you come across a C program that’s stuffed full of functions passing pointers to other functions to manipulate lists, or a chunk of Python that uses some convoluted application of regexes to do math. Or like how Deep Dream reveals that someone at Google was feeding a neural net with a whole pile of dogs.

Where was I going with all this? Oh yeah, that’s right.

I believe that, if not for the absolutely worthwhile help in QBasic, and the bundling

of Nibbles, I might never have developed the interest in programming that I have now.

I also think that programming has generally become less inherently discoverable, and

that’s kind of sad. In theory nowadays you could write something in JavaScript, make a

little HTML file that references it, and open that web page in your browser. Of course,

remember to enable filename extensions in the file manager, and get rid of the .txt

that Notepad adds by default, and yes you need to learn the basics of two separate

languages before making anything!1 And there’s certainly not any thorough,

context-sensitive language reference. In fact, there’s no documentation at all by default.

You just already have to know what you’re looking for, and how to find it. Everything’s

on the internet anyway, why provide anything on the computer?

On the other hand, while it does take some leg work to get started with learning how to program, there’s so much more available now. Modern languages have made QBasic obsolete, and full-featured systems like the Raspberry Pi have replaced those clunky VTech toys. And there’s still books! For that matter, I think they’ve improved quite a bit as well. It’s a pity that things like Python aren’t shipped standard.

Incidentally, if you’re looking, I’d recommend either (or both) of Python for Kids and Teach Your Kids to Code. These books are Python 3-focused, Raspberry Pi friendly, and have a bunch of fun stuff to catch kids’ attention, like some flashy, colorful graphics, and a handful of games. (I think a flaw of many “learn to program” books is they often tend to focus too strongly on reading and writing text, which isn’t altogether captivating and doesn’t invite the reader to learn more.) You don’t need to be a kid, or even a beginner, to enjoy these: I spent maybe an hour sitting on the floor of a bookstore reading through the latter book.

And just in the interest of translating my personal experiences into the present day, I

ported Nibbles to Python and posted it onto Bitbucket.

It’s almost a line-by-line translation, with the original structure intact. It uses the

curses library, so alas it won’t work under Windows, and it’s a bit choppy at times, but

other than that, it should work fine.

Five points to the first person to make a snake/python joke; but ten points to the first person to explain why that joke doesn’t actually work.

-

HTML may not be a Turing-complete language, but it is a language! ↩

Comments