I previously mentioned the

spreadsheet tool sc in my text-mode overview, noting that it deserved a

separate post. It is one of the oldest spreadsheet programs around, maybe

even the oldest still in use today. (The date examples in the documentation

are all from the 1970s, for what it’s worth.)

sc was originally written by James Gosling, who later went on to create the

programming language Java. Like any sufficiently old piece of software,

development is spread across a handful of forks. There’s

at least

three direct forks that I can find, as well

as derivative versions like sc-im.

There also exists a graphical frontend for X11/Athena called Xspread, but I can

no longer find anything resembling a home page for it, and distros seem to have

dropped the package. (It didn’t offer much that sc didn’t, anyway.)

sc has a rather steep learning curve, especially for those not already

passingly familiar with vi-style editing. If you’re expecting a terminal

equivalent of Excel (or OpenOffice, or LibreOffice, or whatever its name is

this year), you will likely be disappointed. Moreover, while it adopts many of

vi‘s principles, only the most basic keystrokes work similarly; it is quite a

different animal. That is, Excel is a dog, vi is a cat, and sc is a fox.

Hope that’s clear.

For heavy command-line users, it’s worth the effort to learn, and fortunately it also comes with plenty of resources to help, including a well-written manual page, a detailed tutorial, and an interactive quick-reference help system. This might be surprising to those used to modern software, but back in The Day, programs generally came with good documentation.

I should also point out, by the way, that I am only covering sc here, and not

sc-im, which has been extensively modified to act much more “vimmy” — for

example, changing the W key to :w. For what it’s worth, I think sc has a

friendlier help system for new users, as it’s concisely broken into

quickly-accessible pages, e.g. ?h displays the row and column commands.

sc-im looks nicer, though, and might feel a little more familiar to vim

aficionados, but it has a few differences I just can’t get past. If you’re

interested, give both a try and see which you prefer.

Here’s a handy cheat sheet for some basic tasks:

| key(s) | function |

|---|---|

? |

help (super helpful!) |

Arrows or hjkl |

move cursor |

Ctrl-A |

move to top-left cell (A0) |

= |

insert a number or formula |

<, \, > |

insert left/center/right aligned text |

{, |, } |

align existing text left/center/right |

e, E |

edit number/string value |

x, Del |

clear cell |

ir, ic |

insert row/column |

dr, dc |

delete row/column |

P |

“put” (save) |

G |

“get” (load) |

If you’re familiar with Excel, you might want to add the following to your

~/.scrc file:

set craction = 1 set numeric

This will enable the familiar behavior of automatically switching to insert

mode when you type a number, and advancing the cursor to the next row down when

you press Enter. This auto-insert only works for numbers, though, since most

of the other keys are taken by vi-style commands.

Numeric expressions, formulas, and ranges also work much like Excel, but row

numbering starts at 0, and functions are preceded with an @ symbol, e.g.

@sum(A0:A20). Also: a cell can contain both a number and a label, which

confused the heck out of me when I was first learning.

A common task when working with spreadsheets is to fill a block of cells with a

value, or a formula (with the row/column references adjusted correspondingly).

To do this, enter the value you want in the first cell. Then, with the cursor

over that cell, type c. – that’s c followed by a period – move the cursor

around to select the range to fill in, and hit enter.

Alternately, to fill a block with different values, first type rf (for

range fill), select the block, hit colon or tab to switch to command

entry mode, and type the start and increment. For example, rf9j:3 3 fills the

first few cells in column A with multiples of three. (For those unfamiliar with

vi notation, 9j there means “move down nine times”.)

Another often-used range function is sorting; rs (range sort) does

that. If you just want to sort ascending by the first column in your range,

you’re in luck, because that’s all you need to remember. Just select visually

and hit enter, and presto, it’s sorted. Otherwise, the incantation is a little

bit on the esoteric side. I learn best from examples, so here’s a few:

| Type this … | to sort like this: |

|---|---|

rs:"+#c |

numeric values in column C, ascending |

rs:"-$a-$b |

text in columns A and B, in reverse |

rs:"+$d+#d |

either text or number in column D, ascending |

The sort criteria is a text value with three pieces: the order (+ for

ascending, - for descending), which kind of value to look at (# for

numeric, $ for text), and the column to sort.

Pressing ‘f’ shifts to a format setup mode, which has its own key map. Formats configured this way apply to the entire column, which is generally what you want.

| key(s) | function |

|---|---|

h/l, ←/→ |

adjust column width |

j/k, ↓/↑ |

adjust decimal precision |

0-9 |

set predefined numeric format |

= |

define numeric format |

Enter |

exit formatting mode |

The predefined formats most likely to be useful for basic tasks are 0 (general number) and either 3 or 4 (dates). Format 4 uses four-digit years, which is usually a good idea, but in a console where screen space is scarce, sometimes shorter is better.

Setting a custom format is somewhat weird: press f=, enter the number for the

format you want to set, and then write the format string. (If you don’t have

set numeric enabled, you can also hit enter and type the commands directly,

and use the arrow keys to get to history items. This is nice for experimenting

with formats.) For an example, this configures slot 7:

f=7$#,0.&

… as a “currency” type, which puts a dollar sign before the value and uses the default field precision.

Custom date formats are similar, though it’s a bit of a hack as the

indicator of a date format is a literal Ctrl-D character. (Yes, it’s weird.)

Dates, by the way, are stored in predictable Unix fashion as time_t values,

and are formatted with strftime(). Since formats 3 and 4 are already preset

for dates, let’s keep all the time values together and define 5 and 6 for a

date-time and time, respectively:

f=5^D%e %b f=6^D%H:%M

(^D here denotes pressing Ctrl-D.) The %-codes are the same as

strftime.

If you’d like to keep these formats permanently, you can put the commands right

into your ~/.scrc just like they were formatted. You’ll have to take care

with date formats though, because they do need that literal Ctrl-D character.

format 5 = "^D%e %b" format 6 = "^D%H:%M" format 7 = "$#,0.&"

Fortunately, sc isn’t quite arcane enough to make you write all your dates as

time_t values for them to show up properly; there are a few other ways of

expressing the date and time. First and probably most useful, a value like

2016.8.12 will be parsed as a date. (Note that the year needs to be four

digits.) This is permuted upon entry into @dts(2016,8,12), which is a formula

that spits out the time_t for midnight on that date. There’s a similar @tts

function for writing time values – and you can even add the two together if

you want to define a date and time. It’s a bit awkward, but hey, it works,

and the scaffolding makes a lot more sense than Excel’s weird decimal numbers.

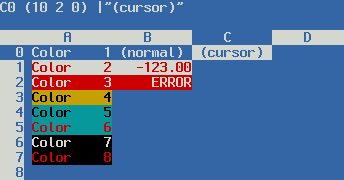

sc admittedly isn’t the prettiest program, either, but if you put set color

in your ~/.scrc, you can at the very least use a handful of alternate color

combinations, and even set some of your own. Try entering a bunch of data, move

to the top, and press rC (range Colors), select a block, then hit

colon and the number of the color you’d like. Or rather, it’s a color pair, a

somewhat awkward concept that got inherited from curses, but the point is,

each number is a cell style.

The defaults, though, are butt ugly:

If you want less gross colors, check out the manpage and edit ~/.scrc

accordingly.

There’s a couple other color-related settings you might be interested in. set

colorneg increments the color value by one if the value in the cell is

negative – in other words, if a cell is using the default color 1, negative

numbers will display in color 2 instead. There’s also set colorerr, which

highlights formula errors in color 3. I use both of these, and generally set

colors 4-8 for headers and various other cells that deserve some sort of

attention, much like one might use bold or italic text.

One last feature I will cover is framed ranges. This is a way to define cells

that “stick” when the spreadsheet scrolls, and in its basic form, a framed

range is roughly like Excel’s “freeze” feature. I find it most useful to use

the command line to define these, especially for larger frames, but you can

also select the ranges interactively if you prefer by typing rra. Either way,

the syntax is:

frame outrange inrange

where outrange and inrange are both ranges, e.g. A0:D50. Supposing you’d

like to have a “header” of column A and row 0 that stays on the screen all the

time, for the whole sheet. In this case, your outrange would be A0:Z199 (or

however far you want to extend it — I don’t think it’s possible to say “the

whole spreadsheet” here), and inrange would correspondingly be B1:Z199. So

the final syntax for this setup would be:

frame A0:Z199 B1:Z199

… thus effectively locking the first row and first column so long as the cursor is inside the inner range that you’ve defined. Frames can do a lot, but this basic usage is sufficient for most of my needs, and probably for yours as well.

There’s a lot more under the hood, especially if you take the time to get to learn all the little nuances of how things work. It is worth spending a weekend sifting through the documentation and experimenting with all the commands. The range commands and row/column commands are especially worth giving some attention.

Lastly, I should point out one important point about security: sc provides

multiple ways to embed the execution of arbitrary commands into a spreadsheet.

This can be powerful, but with great power comes great responsibility — don’t

just blindly load random spreadsheets you found on the internet! (I considered

making an example spreadsheet to accompany this article, but decided against it

for this reason.)

Comments